Question of the Week 558

Author: Anila B. Elliott, MD - University of Michigan - C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital

A 14-year-old with a history of idiopathic cardiomyopathy with a HeartMate III LVAD in place presents for elective EGD and colonoscopy for intermittent and vague abdominal pain. They are hemodynamically stable and currently asymptomatic. Their initial device parameters are listed below:

What is the best course of action?

What is the best course of action?

EXPLANATION

The use of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices (VADs), such as the HeartMate III, has increased among adolescents requiring mechanical circulatory support. This shift has been driven by advances in technology, improved outcomes, and broadening indications for bridge to transplant and destination therapies. Historically, the Berlin Heart EXCOR was the main FDA-approved device available in children; however, adolescents who are appropriately sized are increasingly undergoing HeartMate III implantation1,2. Outpatient management is now feasible for more pediatric patients, contrasting with the dependency on inpatient status required by the Berlin due to the Ikus system1. Notably, nearly one-third of children undergoing heart transplantation in the United States are now bridged with VADs, which is impactful given the high pre-transplant morbidity and mortality in this patient population paired with the limited supply of organs for transplantation2,3.

Although pediatric experience informs much of our VAD management in the congenital cardiac patient population, foundational adult trials have shaped the field. The REMATCH trial showed improved survival with long-term VAD support for those not candidates for transplantation (destination therapy)2. More recently, the MOMENTUM study highlighted that 3rd-generation devices (HeartMate III) are associated with fewer complications including pump thrombosis, bleeding, stroke and arrhythmias compared to older devices4,5. This data is increasingly relevant to older children and adolescents who have access to those devices.

Understanding the device mechanics and settings is essential for optimal peri-operative care. The VAD has an inflow cannula typically in the left ventricle that pumps blood to an outflow cannula in the ascending aorta. The pump is powered and regulated by a controller that is connected to the pump by the driveline, which is powered by an external battery or stable AC power supply. Compared to previous versions of VADs, the HeartMate III has a magnetically levitated rotor, which reduces blood friction and decreases the risk of thrombotic and hemolytic complications4.

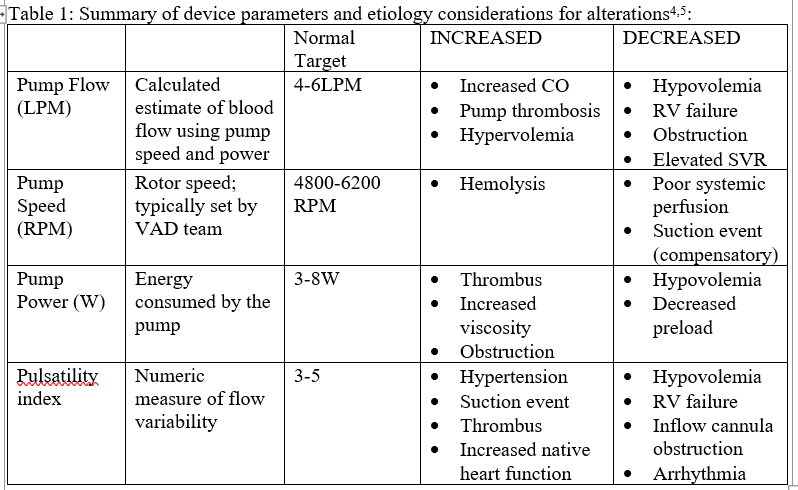

At the time of implantation, pump speed is typically initially set around 3000RPM and slowly titrated to balance effective ventricular unloading with residual LV ejection. The controller measures the power required to achieve the set pump speed. Pump speed, power and hematocrit are used by the device to calculate pump flow. Pump flow should be used as a trend as it can differ from actual flow by 15-20%. The device also calculates pulsatility index which is a measure of power fluctuation4.

Up to one-third of patients require admission within 6 months of implantation, with the most common etiology being gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding1. Other complications include infection, stroke, thrombosis, RV failure, and multi-organ dysfunction. When presenting for noncardiac procedures, VAD patients have increased 30-day mortality, readmission, major adverse cardiac events (MACE), intraoperative hypotension, and malignant arrhythmias.

Continuous-flow VADs are preload-dependent and afterload-sensitive. Sufficient ventricular preload is required to maintain pump output, while excessive afterload diminishes flow. Low preload or high afterload will reduce pump flow and/or produce alarms4,5.

A “suction event” occurs when insufficient preload results in partial collapse of the ventricle and obstruction of the inflow cannula, which causes an acute decrease in pump flow and power. HeartMate III devices are programmed to detect an impending or actual suction event using pulsatility index detection, which allows the pump to transiently reduce the pump speed by 200-400RPM to compensate. Supportive management consists of fluid bolus administration to correct volume deficits, with incremental speed adjustments as indicated by a VAD specialist if needed.

In this scenario, the decreased flow, speed, and power with increased PI are classic indicators of a suction event, likely precipitated by volume depletion from a possible slow GI bleed, which makes option A, a fluid bolus to improve preload as the best next course of action. Other options on the differential include RV failure, inflow cannula obstruction, or arrhythmias.

Elevated PI can also occur in hypertension, pump thrombosis, or when native cardiac function increases suddenly4,5. Table 1 is a summary of VAD parameters and management in the peri-operative period.

REFERENCES

1. Burki, S., Adachi, I. Pediatric ventricular assist devices: current challenges and future prospects. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2017; 13:177-185

2. Adachi, I., Burki, S., Zafar, F., et al. Pediatric ventricular assist devices. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2015; 7(12); doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.61

3. Mokshagundam, D., Rosenthal, DN., Smyth, L., et al. Bridging gaps in pediatric device development: The power of ACTION—a collaborative learning network. The Journal of Hearth and Lung Transplantation 2025; 44(4): 541-544

4. Belkin, MM., Kagan, V., Labuhn, C., et al. Physiology and Clinical Utility of HeartMate Pump Parameters. J Card Fail 2021; 28(5):845-862

5. Falland, R., Allen, SJ. Perioperative management of patients with a ventricular assist device undergoing non-cardiac surgery. BJA Educ 2023; 23(10):406-413