Author: Meera Gangadharan, MD, FASA, FAAP - University of Texas at Houston

A four-year-old male presents for computed tomography of the brain due to a history of seizures in setting of playing soccer. During inhalational induction, the patient becomes fearful and anxious with a heart rate of 190. Within seconds, there is an abrupt change in the ECG from normal sinus rhythm to a wide-complex, bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, which proves unresponsive to epinephrine. A baseline electrocardiogram was normal. What is the MOST likely diagnosis?

EXPLANATION

The cardiac channelopathies are a heterogeneous group of arrhythmias that are associated with sudden cardiac death. The etiology is typically abnormal function of the sodium, potassium, and/or calcium channel within the myocardial cell membrane. There is a strong genetic component and, therefore, obtaining a detailed family history and genetic testing is essential. Clinical features include syncope, seizures, or sudden cardiac death.

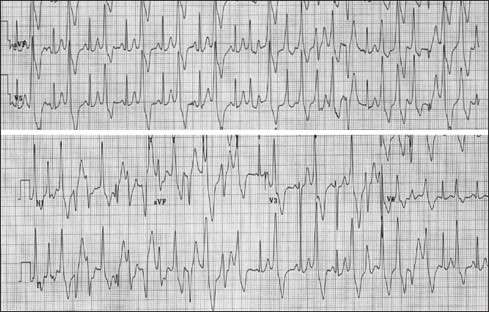

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is an inherited, congenital arrhythmia which usually manifests in children and young adults as dizziness, presyncope, syncope, seizures (secondary to syncope), and sudden cardiac death. It has an incidence of approximately one in 10,000. CPVT is characterized by a rapid polymorphic and bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (VT) occurring during physical exercise or emotional stress – see image below, used under Creatice Commons License. These patients are asymptomatic at rest and have normal resting electrocardiograms without structural cardiac abnormalities.

Electrocardiogram during exercise stress testing demonstrates increasing frequency of ventricular arrhythmias, degrading from bigeminy to a typical bidirectional ventricular tachycardia. From Behere SP, Weindling SN. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: An exciting new era. Ann Pediatr Cardiol .2016;9(2):137-146. doi:10.4103/0974-2069.180645. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4867798/

CPVT is caused by abnormal intracellular regulation of calcium in the cardiomyocyte resulting in ventricular ectopy, polymorphic couplets, ventricular fibrillation (VF), and ventricular tachycardia (VT) with a characteristic bidirectional morphology. Autosomal dominant mutations in the ryanodine receptor 2 (RYR2) gene account for 60-70% of cases, and autosomal recessive mutations in the calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) gene account for an additional 10-15% of CPVT cases. Although most cases are familial, some individuals may present with de novo mutations in the absence of a family history of CPVT.

The five therapeutic options for the treatment of CPVT include the following: (1) lifestyle modifications; (2) beta-blockers; (3) implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD); (4) flecainide; and (5) left cardiac sympathetic denervation. Life-style changes include avoiding triggers that cause increased sympathetic activity such as strenuous exercise and competitive sports. However, patients can partake in sports if they are asymptomatic and compliant on their medical regimens. Long-acting beta blockers, such as nadolol, are first line medical therapy. Flecanide can be effective in patients who are symptomatic despite maximal beta blocker therapy. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) is an effective option for patients who are still symptomatic despite maximal medical therapy. LCSD involves resection of the lower half of T1 and parts of the T2, T3 and T4 thoracic ganglia. Typically, ICD insertion is reserved for patients who are not fully responsive to medical therapy. However, ICD implantation may lead to several undesirable and potentially life-threatening complications and side effects, including the following: (1) inappropriate defibrillation; (2) catecholamine surge due to device discharge, which can potentially cause a “storm” of ventricular tachycardia, and (3) complications related to the device such as pocket infection, lead fracture and displacement, endocarditis, vessel stenosis, and need for reimplantation of the ICD. In a systematic review of 53 studies describing 1,429 patients with a median age of 15 years and CPVT treated with ICD placement, 19.6% of patients experienced a storm which resulted in the death of 1.4% of patients.

It is important to have a high index of suspicion for CPVT in patients with a history of syncope with intense exertion, as epinephrine can be detrimental and cause further deterioration. Bellamy et al described three patients with the diagnosis of CPVT. Collectively, there were two episodes of ventricular tachycardia and one episode of ventricular fibrillation that were unresponsive to repeated doses of epinephrine but that resolved with administration of opiates. Two patients were rescued with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and then underwent epinephrine challenge that resulted in polymorphic, bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, thereby confirming the diagnosis of CPVT.

Long QT syndrome is characterized by the hallmark feature of prolongation of the QT interval on ECG, reflecting delayed myocardial repolarization, and is unlikely in this case as the patient had a previously normal ECG. Other hallmark features include polymorphic VT leading to syncope and sudden death. Brugada syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in the right ventricular outflow tract, which are responsible for characteristic ECG changes and the development of polymorphic VT/VF. The key diagnostic feature of Brugada syndrome is the presence of a “type I Brugada ECG pattern “in the right ventricular leads on the 12 lead ECG. This consists of a partial right bundle branch block, J point elevation, and coved ST segment elevation followed by a T wave inversion. Brugada syndrome is unlikely in this patient with a previously normal ECG.

REFERENCE

Kim CW, Aronow WS, Dutta T, Frenkel D, Frishman WH. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Cardiol Rev . 2020;28(6):325-331. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000302

Mellor GJ, Behr ER. Cardiac channelopathies: diagnosis and contemporary management [published online ahead of print, 2021 Feb 15]. Heart .2021;heartjnl-2019-316026. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2019-316026

Bellamy D, Nuthall G, Dalziel S, Skinner JR. Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: The Cardiac Arrest Where Epinephrine Is Contraindicated. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(3):262-268. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001847

Roston TM, Jones K, Bos M et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: A systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2018; 15:1791-1799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.06.046