Authors: Meera Gangadharan, MBBS, FAAP, FASA - Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital/McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX and Destiny F. Chau, MD - Arkansas Children’s Hospital/ University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR

A 10-year-old patient with an extra-cardiac Fontan is undergoing a cardiac catheterization to evaluate recent-onset shortness of breath and productive cough. Shortly after endotracheal intubation, the peak airway pressure is 40 cm H2O along with diminished bilateral breath sounds and decreasing end tidal CO2 on capnography. The systemic oxygen saturation falls from 83% to 68% with no response to albuterol or intravenous epinephrine. Which of the following diagnoses is the MOST likely etiology for this clinical scenario?

EXPLANATION

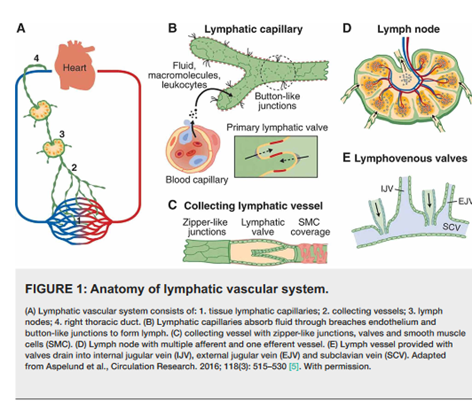

The Fontan circulation is characterized by a high central venous pressure necessary to drive blood through the pulmonary vascular bed in the absence of a subpulmonary ventricle. At the level of the capillary bed this imposes greater demands on the lymphatic system to clear fluid from the interstitial tissue. Lymphatic capillaries are thin-walled vessels that connect to larger vessels called lymphangions, which propel lymph toward the lymph nodes and eventually to the thoracic duct or the right lymphatic duct. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. Anatomy of lymphatic vascular system. (From Ahmed MA. Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0.)

Chronically high central venous pressures, typical of the Fontan circulation, causes increased production of lymphatic fluid by the liver. As a result, lymphatic vessels dilate to accommodate changes in capillary bed filtration. Lymphatic congestion with subsequent lymphatic fluid leak results in downstream pleural fluid accumulation, plastic bronchitis, ascites, and protein losing enteropathy.

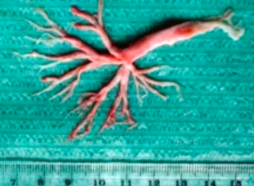

Approximately 5% of Fontan patients develop plastic bronchitis, a condition characterized by the exudation of protein-rich lymphatic fluid into the bronchial airways with the formation of casts. The casts are typically described as having a rubber-like consistency and taking the shape of the containing airways (See Figure 2). Casts are thought to develop from the crosslinking of fibrin within the lymphatic fluid contained in the airways and may lead to complete airway obstruction. Patients may present with wheezing, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, fever, hypoxia, and a cough productive of casts. In addition to Fontan patients, plastic bronchitis has also been reported in patients with asthma, sickle cell disease, infectious and allergic conditions, cystic fibrosis and lymphatic malformations.

Figure 2. Bronchial cast. (From Pałyga-Bysiecka et al. Creative commons attribution license (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/)

Treatment consists of facilitating the physical removal of bronchial casts by expectoration or bronchoscopy. Inhaled bronchodilators, N-acetylcysteine, dornase alpha, DNase, inhaled heparin, and tissue plasminogen activator are prescribed to facilitate expectoration. Corticosteroids may be administered to reduce inflammation, a possible contributing factor. Interventions to reduce the extravasation of lymphatic fluid include: 1) intervention/treatment to reduce Fontan pressure and, 2) MRI-guided lymphangiography with lymphatic vessel interventions to disrupt communications with the airway. Fontan patients are typically evaluated for physical obstruction within the Fontan pathway and high pulmonary vascular resistance, both of which impede blood flow and increase upstream pressure. Targeted interventions may include creating or enlarging a Fontan fenestration, relieving physical obstruction with stents or balloon angioplasty, or medical treatment with pulmonary vasodilators. Furthermore, patients with severe valvular regurgitation may necessitate valve repair/replacement. Likewise, the presence of arrhythmias may require cardiac resynchronization and anti-arrhythmic medications. Refractory Fontan failure can lead to Fontan take-down or heart transplantation.

Anesthetic management for bronchoscopy and removal of airway casts can be fraught with complications. Singhal et al describe the periprocedural course of two pediatric patients with Fontan physiology who developed hemodynamic instability, hypoxemia and hypercarbia during bronchoscopy for removal of bronchial casts. One patient was managed with multiple vasoactive agents and stress-dose steroids due the development of septic shock while the second patient required veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation due to cardiorespiratory failure.

The patient described in the stem presents with respiratory distress and productive cough. After intubation, high peak airway pressures and decreased oxygen saturation may be due to any of the answer choices. However, tension pneumothorax is doubtful given the presence of bilateral breath sounds. Further, the patient is unresponsive to treatment with albuterol and epinephrine, making bronchospasm unlikely. Given the known complications of Fontan physiology and the clinical presentation, this patient most likely has plastic bronchitis and major airway obstruction from bronchial casts.

REFERENCES

Pałyga-Bysiecka I, Polewczyk AM, Polewczyk M, Kołodziej E, Mazurek H, Pogorzelski A. Plastic bronchitis-A serious rare complication affecting children only after Fontan procedure? J Clin Med. 2021; 11(1):44. doi:10.3390/jcm110100

Rychik J, Atz AM, Celermajer DS, et al. Evaluation and management of the child and adult with Fontan circulation: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019; 140(6):e234-e284.

Li Y, Williams RJ, Dombrowski ND, et al. Current evaluation and management of plastic bronchitis in the pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020; 130:109799. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109799

Singhal NR, Da Cruz EM, Nicolarsen J, et al. Perioperative management of shock in two Fontan patients with plastic bronchitis. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013; 17(1):55-60. doi:10.1177/1089253213475879

Ahmed MA Sr. Post-operative chylothorax in children undergoing congenital heart surgery. Cureus. 2021; 13(3):e13811. doi:10.7759/cureus.13811