Authors: Anuradha Dev, MD and Marc Atwell MD - Georgetown Public Health Corporation (GPHC), Georgetown, Guyana AND Destiny F. Chau, MD - Arkansas Children’s Hospital/University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR, USA

A 10-year-old boy presents with shortness of breath and declining exercise capacity. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrates a double chamber right ventricle. Which of the following percentages reflects the approximate number of patients with double chamber right ventricle with a concurrent ventricular septal defect?

EXPLANATION

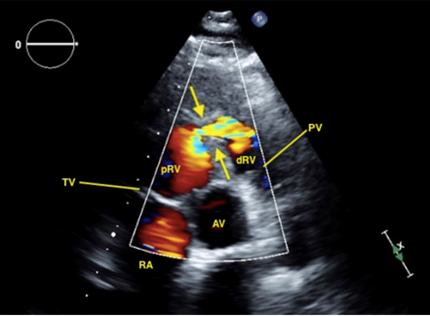

Double chamber right ventricle (DCRV) is a rare cardiac diagnosis reported in up to 2.6% of patients with congenital heart disease. It typically presents in childhood with few cases reported in adults. DCRV is described by a sub-infundibular tissue substrate within the body of the right ventricle (RV) that leads to progressive RV outflow obstruction. The obstructing tissue has been identified as hypertrophied trabecular muscle bands and/or atypical moderator bands that divide the RV into a proximal high-pressure inlet chamber located close to the apical region of the RV and a distal low-pressure outlet chamber located near the infundibular region. There is typically an increased pressure gradient greater than 20 mmHg across the two chambers (see Figure below).

It is hypothesized that the anatomical substrate for DCRV is often present at birth. For example, congenital cardiac defects that create flow turbulence may trigger tissue hypertrophy leading to obstruction within the RV cavity. Although over 75% of DCRVs are associated with ventricular septal defect (VSD), it is also associated with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), double outlet right ventricle, and Ebstein anomaly. The VSD of DCRV is usually small and perimembranous. Although it may be located in any location along the interventricular septum, the VSD usually connects with the proximal high-pressure inlet chamber. The resulting pathophysiology is due to shunt flow characteristics as determined by the location of the VSD in relation to the obstruction within the RV. When the VSD is distal to the obstructing muscle bundle, the resulting physiology is akin to an isolated VSD, but when the VSD connects to the RV proximal to the muscle bundle, the physiology is akin to tetralogy of Fallot.

Figure: Two-dimensional TTE with color-flow Doppler. Parasternal short-axis view at the aortic valve level in end systole demonstrates muscular septation of the RV into a high-pressure proximal chamber and low-pressure distal subvalvular chamber. Arrows indicate RV muscular bundles causing subvalvular obstruction. AV= aortic valve, PV=pulmonic valve, TV=tricuspid valve, RA=right atrium, pRV=proximal RV, dRV=distal RV.

From Malone RJ, Henderson ER, Wilson ZR, et al. Double-chambered right ventricle in adulthood: a case series. CASE (Phila). 2024;8(3Part A):202-209. doi:10.1016/j.case.2023.12.012. Creative Commons Licensing 4.0.

Figure: Two-dimensional TTE with color-flow Doppler. Parasternal short-axis view at the aortic valve level in end systole demonstrates muscular septation of the RV into a high-pressure proximal chamber and low-pressure distal subvalvular chamber. Arrows indicate RV muscular bundles causing subvalvular obstruction. AV= aortic valve, PV=pulmonic valve, TV=tricuspid valve, RA=right atrium, pRV=proximal RV, dRV=distal RV.

From Malone RJ, Henderson ER, Wilson ZR, et al. Double-chambered right ventricle in adulthood: a case series. CASE (Phila). 2024;8(3Part A):202-209. doi:10.1016/j.case.2023.12.012. Creative Commons Licensing 4.0.

Patients with severe RVOT obstruction typically present with dyspnea on exertion and limited exercise capacity. Echocardiography is a good first-line screening tool for many cardiac defects, but the identification of DCRV may often be overlooked unless there is a high index of suspicion. Other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging or cardiac catheterization can confirm the diagnosis of DCRV. Surgery involves transatrial or transventricular resection of the obstructing muscle bundles and a VSD closure. Survival rates in the current era are excellent. However, there is the potential for a right bundle branch block or complete heart block.

The correct answer is C, over 75% of patients with DCRV also have an associated VSD.

REFERENCES

Loukas M, Housman B, Blaak C, Kralovic S, Tubbs RS, Anderson RH. Double-chambered right ventricle: a review. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(6):417-423. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2013.03.004

Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019.14;73(18):2361]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):1494-1563. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1028

Said SM, Burkhart HM, Dearani JA, O'Leary PW, Ammash NM, Schaff HV. Outcomes of surgical repair of double-chambered right ventricle. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(1):197-200. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.043

Kahr PC, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Kempny A, et al. Long-term natural history and postoperative outcome of double-chambered right ventricle--experience from two tertiary adult congenital heart centres and review of the literature. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):662-668. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.177

Hubail ZJ, Ramaciotti C. Spatial relationship between the ventricular septal defect and the anomalous muscle bundle in a double-chambered right ventricle. Congenit Heart Dis. 2007; 2:421-423.