Sana Ullah, MB ChB, FRCA - Children’s Medical Center, Dallas

A 16-year-old girl had a syncopal episode at home while watching television. She had a concurrent viral illness with a high fever. There was no previous history of syncope or palpitations and no family history of sudden death. Vital signs after the event were the following:

Heart rate: 80 beats per minute

Blood pressure: 120/70

Pulse oximetry 97% on room air

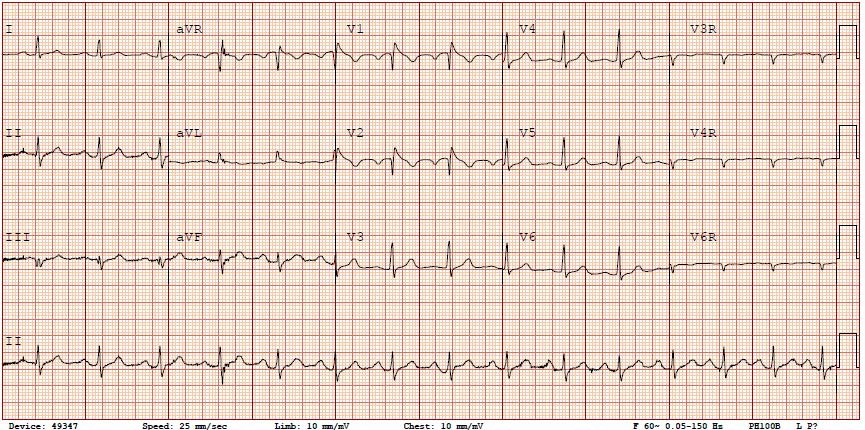

A 12-lead ECG was completed – see image below. An echocardiogram revealed no structural cardiac abnormalities. What is the MOST APPROPRIATE next step in the management of this patient?

Correct!

Wrong!

Question of the Week 322

The ECG is consistent with a diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome (BrS). First described in 1992, BrS is an inherited channelopathy of the cardiac sodium channels. It is associated with a characteristic ECG pattern of “coved-type” ST-elevation in leads V1-V3 and a right bundle branch pattern, which predisposes to a high risk of sudden death due to ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation [1, 2]. Sudden death frequently occurs at rest or during sleep. It has frequently been seen in young Asian males where it has been termed “sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome.” Fever is a well-recognized precipitating factor, although the precise mechanism is still debated. In approximately 20% of patients, it is associated with a loss of function mutation in the SCN5A gene, which is also found in Long QT3 syndrome. In a multi-institution study of 30 children with BrS, the two most common etiologies were family history of BrS and unexplained syncope that was precipitated by fever in half of those children [3]. Diagnosis is usually based on the clinical history and the pathognomonic ECG abnormalities. However, the ECG abnormalities may be intermittent, and in these cases, a specific Brugada ECG protocol may be necessary with the use of sodium channel blocking drugs such as ajmaline, procainamide or flecainide. An ECG during a febrile episode may also be helpful.

Treatment of BrS includes general measures such as aggressively treating a febrile illness with antipyretic medication and avoidance of certain medications, which can be found on a website – www.brugadadrugs.org.

For adult patients with a diagnostic ECG, history of syncope or a family history of sudden death, the definitive treatment is ICD placement. If an ICD is contraindicated, quinidine has been used for treatment.

In children, the use of ICDs is less studied in comparison with adults and is a much more difficult clinical decision. Although ICDs can prevent sudden death, there is a significant incidence of device complications and inappropriate shocks [4].

In this patient, a brain CT is unlikely to show any abnormality in the absence of a neurological deficit. Watchful waiting is not appropriate based on the history and diagnostic ECG. A cardiac MRI is unlikely to be helpful in the presence of a structurally normal heart as seen on echocardiography. However, a cardiac MRI does have utility if a structural cardiomyopathy is suspected as a cause of aborted sudden death.

References

1. Brugada J, Campuzano O, Arbelo E et al. Present status of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 1046-1059.

2. Behere SP, Weindling SN. Brugada syndrome in children – Stepping into unchartered territory. Ann Pediat Card. 2017; 10: 248-258.

3. Probst V, Denjoy I, Meregalli PG et al. Clinical aspects and prognosis of Brugada Syndrome in children. Circulation. 2007; 115: 2042-2048.

4. Corcia MCG, Sieira J, Pappaert G et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in children and adolescents with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71: 148-157.

Treatment of BrS includes general measures such as aggressively treating a febrile illness with antipyretic medication and avoidance of certain medications, which can be found on a website – www.brugadadrugs.org.

For adult patients with a diagnostic ECG, history of syncope or a family history of sudden death, the definitive treatment is ICD placement. If an ICD is contraindicated, quinidine has been used for treatment.

In children, the use of ICDs is less studied in comparison with adults and is a much more difficult clinical decision. Although ICDs can prevent sudden death, there is a significant incidence of device complications and inappropriate shocks [4].

In this patient, a brain CT is unlikely to show any abnormality in the absence of a neurological deficit. Watchful waiting is not appropriate based on the history and diagnostic ECG. A cardiac MRI is unlikely to be helpful in the presence of a structurally normal heart as seen on echocardiography. However, a cardiac MRI does have utility if a structural cardiomyopathy is suspected as a cause of aborted sudden death.

References

1. Brugada J, Campuzano O, Arbelo E et al. Present status of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 1046-1059.

2. Behere SP, Weindling SN. Brugada syndrome in children – Stepping into unchartered territory. Ann Pediat Card. 2017; 10: 248-258.

3. Probst V, Denjoy I, Meregalli PG et al. Clinical aspects and prognosis of Brugada Syndrome in children. Circulation. 2007; 115: 2042-2048.

4. Corcia MCG, Sieira J, Pappaert G et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in children and adolescents with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71: 148-157.